#2 The Special Place of the Qur'an in Ibn 'Arabi with Dr E Winkel

Summary

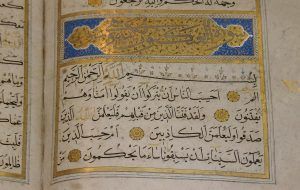

In this podcast, we continue alongside Dr Eric Winkel (Shuʿayb) to unpack the multifaceted voluminous work of Ibn al-ʿArabī—the translation of the Futūḥāt al-Makkīyah, a project that spans over 10 years in the works and counting! He provides an update about the complimentary visual works that draws meaning from imagery for the 28 or so concepts needed to understand Ibn al-ʿArabī (An Illustrated Guide to Ibn al-ʿArabī, concerted with the Islamic Creative Imagination, now available on Pir Press) and explains how creative art and visualization have been...

immensely beneficial for translation.

Ibn al-ʿArabī see things visually—letters, grammatical forms, and syntax; they all form a world of their own, a universe of rules and meaning through which الله (Allāh), God, communicates with us. Through visualization, one taps into the portal for the imaginal realm and arriving at greater intrinsic meaning becomes possible. Eloquently expressed, as illustrated, by Sidi Shuʿayb.

To access this shoreless ocean comprised of multilayered meanings, Shuʿayb also looks at the root words of the Arabic language with quite a literal approach to interpreting the Qurʾān. By bringing the implicit forward, conscious understanding manifests and the message of Islām, from the outward شريعة(sharīʿa) to the inward طريقة (ṭarīqa), continues to propagate as a wave form in the universe. A deep learning opportunity for the listener arises through Shuʿayb’s detailed discussion on the Nūr Muḥammad ﷺ, relayed in context of the ḥadith in which ʿĀʾisha r.a. says that ‘His character was the Qurʾān.’

Steering with the theme of this podcast, the Qurʾān in the works of Ibn al-ʿArabī, we delve into specific verses and passages. Shuʿayb explains: every page has an honoring of the Prophet ﷺ and every page has many verses of Qurʾān and they’re very much connected. The potential permutation of meaning from a linguistic undertaking reminds us of the importance of إجتحاد (ʾijtiḥād) and the myriad عقيدة (ʿaqīdas) underlying a spiritual walking. As Sidi Shuʿayb touches on in this podcast,طحقيق (ṭaḥqīq), our internal validation, becomes essential to uncovering our story and the story of creation.

Once again, Ibn al-ʿArabī’s role as a dragoman reminds us that through the special face of حق (Ḥaqq) in every created being the تجلی (tajallī) of Allāh hits, yielding depth to the phrase Islām, in surrender, is the دين (dīn) of Allāh. Every person is painted a unique picture through the means that Allāh reveals Himself, never twice to two people nor the same way twice, allowing each individual thread of creation to be carried forward into the world as a unique expression of truth.

So in contrast to the negative connotation traditionally derived from scholarly works for example with a concept such as كفر (kufur), this conversation extends an invitation to a change in viewpoint where the word كافر(kāfir), through inflection, can also mean the people who cover up their station, beautifying revelation. Other words with inflected meanings are examined in context of the respective Qurʾānic sūras.

Together, we explore the subtle nuances. We begin to taste, through a seamless transmission of love, the paradoxical nature, and perplexing depth, of what it means to hold close proximity to the Divine—taking off the covering of those who are drawn near. The kind of love experienced by the ʾawliyāʾ—the friends of God, lovers of the Divine Truth, al-Ḥaqq.

The Special Place of the Qurʾān in Ibn al-ʿArabī

SPEAKERS

Host: Saqib Safdar

Guest: Dr Eric Winkel (Shuʿayb)

Saqib

Greetings, السلام عليكم (as-salāmu ʿalaykum) my name is Saqib, and welcome to another episode of The Ḥikmah Project podcast. I have taken a bit of a break and الحمد لله (al-ḥamdulillāh) back with a new episode with Dr Eric Winkel. If you're listening to this podcast in رمضان (Ramaḍān), رمضان كريم (Ramaḍān Karīm) to you and may you receive the blessings of this blessed month.

In this podcast we speak to Dr Eric Winkel or سيدي شعيب (Sidi Shuʿayb) on the relevance of the Qurʾān on the teachings of ابن عربي (Ibn al-ʿArabī). We look at how his work isn't necessarily a commentary on the Qurʾān, but rather is deeply immersed in the Qurʾān and how he's able to access this shoreless ocean through looking at quite a literal approach to interpreting the Qurʾān. He's not a literalist but looks at the root words of the Arabic language to be able to derive multiple levels of meaning, as Sidi Shuʿayb will explain.

Thank you to those who are who have subscribed to our Patreon subscription and are supporting the project. You can find out more details on the hikmahproject.com as well as visit our Facebook page and social media sites on Instagram and Twitter.

So without further ado, here's the podcast.

Saqib

Okay, as-salāmu ʿalaykum. Welcome, Dr Winkel.

Shuʿayb

السلام عليكم ورحمة الله وبركاته (as-salāmu ʿalaykum wa-raḥmatullāhi wa-barakātuhu).

Saqib

Wonderful to have you again as our guest.

Shuʿayb

Thank you. I'm glad to be here, al-ḥamdulillāh.

Saqib

So Sidi, could you maybe start off just by telling us or giving us an update on your translation work with the الفتوحات المكية (Futūḥāt al-Makkīyah) of Ibn al-ʿArabī.

Shuʿayb

Okay, so for the first… well, I ended up doing many, many, many drafts of the translation. In fact, with chapter one a few years ago, I found out how many times I visited the file chapter one and it was already in the thousands—so I make drafts all the time. And so I'll say first draft, but it means like the first 10 drafts. So right now, I'm at about book 28, with a draft, which has been over about 10 times or so, which except for the kind of editing that Rowan Hayes does for us, it's very much ready. It's been translated. And so all the way up to book 28 is pretty much where I am right now. So I've kind of, instead of moving onwards from there, I've been concentrating on getting the earlier books ready for Rowan and also getting them ready for publication. And so right now, we hope to be having book volume five, which means book nine and 10, volume six, which is 11 and 12 and volume seven, and eight; we may even go up to volume eight by the end of this year إن شاء الله (ʾinshāʾllāh). So we're ready to move quite quickly. It's been 10 years now since I started the project in its exclusive and all consuming way. That's been 10 years now and so I think things are going to be moving quickly now; so that's there.

And then parallel to this work, I've done all those Friday sessions and we did all the way through from 2021; 2020-2021, so we've done all of these Friday sessions every week. And so they're all on YouTube now; and the visuals, what I've done is I've collaborated with an artist of the Islamic Creative Imagination, and we've come up with a way of understanding the 28 or so concepts that you need to understand Ibn al-ʿArabī and we've come up with an illustrated or visual way to do that and the product is An Illustrated Guide to Ibn al-ʿArabī. Pir Press is publishing and it is already coming out. I’m getting my copies; my copies are on their way right now, and people have already been getting their copies when they pre ordered. So that's on Pir Press. So go to www.pirpress.com and you'll see the illustrated guide to Ibn al-ʿArabī.

And so this is something that's so much helped the translation work because it's really pushed me to visualize things, to see things… Ibn al-ʿArabī sees things very visually and all of these, like when he sees letters, he sees beings, he sees human beings and he sees these أولياء (ʾawliyāʾ) and their letters and their grammatical forms and he sees syntax everywhere, he sees grammar everywhere. And that used to be the way, I mean like some others used to see that the universe is a grammar, because there are certain rules that are followed for communication. And so الله (Allāh) follows rules in the universe so that he can communicate with us. So it is very visual, it's very graphic, and close and palpable. Ibn al-ʿArabī sees these things very physically as well. So we will be wanting to do some more work after this, which will go parallel with the translation project.

Saqib

Wow, fascinating! And Sidi, just for our listeners, who may not have delved into the Meccan Openings or the Futūḥāt al-Makkīyah, how many books are there altogether?

Shuʿayb

Yeah. So there are 37 books. So we’re at book 28 right now; 28-29, somewhere in there. And the other translations I have are very rough from that till the end, and I've been putting two books in each volume. So volume one is book one and two, then three, and four is volume two. Because the books, the 37 books, are very much part of what Ibn al-ʿArabī, he uses the جزء (Juzʾ), the manuscript part, and then he uses the Book, and so that's the vision; and then I'm putting two books in a volume. So we're looking at 19 volumes, and so 19 volumes will be stacked up pretty high; we're looking at… it's probably about six feet tall or two meters tall, once we get all the books stacked up, so it's getting quite immense. It'll probably be 12,000 pages, the Arabic is about 10,000 pages.

Saqib

Fascinating. So Sidi, today's theme, is the Qurʾān in the works of Ibn al-ʿArabī, or more specifically, the Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya. Could you just start off by explaining of how important into Qurʾān is Ibn al-ʿArabī’s work?

Shuʿayb

Yes. The one thing that people when they begin to see the work that I'm doing— the Openings Revealed in Mecca, that translation, it's translation and commentary, and it's also meant to be very much complete, so it's not excerpted or something like that, it's the complete translation.

And so one thing that people notice, well, the first thing that you might notice is that the chapters all start with: Learn. So the imperative learn (اعلم). So this is all something that Ibn al-ʿArabī wants us to understand and learn for ourselves. Another thing they'll see is that they'll seeصل الله عليه وسلم (ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam, ﷺ) everywhere and in the manuscript, the actual handwritten manuscript, he doesn't do any honorific sort of medallions or anything or any kind of abbreviation, he writes out: ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam, and it takes up about half of the page of the manuscript. So, if he was trying to be a little more concise, he would have come up with an abbreviation, but he doesn't and that shows the importance of honoring the Prophet Muḥammad ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam every time.

So what I do is to make it way easier for the reader, I put a medallion there — ﷺ — and the ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam, in Arabic, and then the readers can read that and they can make the text flow in a way that the traditional reader has no problem hearing that all the time, it flows still. But for the readers nowadays, to make things flow, it's important to have it as a medallion. So that's how we have it there.

And so the first thing that we'll see is how many mentions there are of the Prophet ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam, it's absolutely central to everything he does. And then they'll also notice the Qurʾān. And the Qurʾān is, I’ll look at this one page, a random page, one verse, second verse, three verses; three verses on that page; here we go: one, verse two, verse three, verse four, verse…, five verses on that page. So the verses are always there, they're everywhere, every page has an honoring of the Prophet ﷺ and every page has a verse of Qurʾān and many verses of Qurʾān. And those last two, these things are actually quite connected, and they're quite connected in a way that is also, it's in a sense, it's implicit, and so it's not necessarily spoken explicitly, it's implicit everywhere, everything Ibn al-ʿArabī does, is making something very implicit about the Qurʾān and the Prophet ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam. And so I guess I can bring that up right now, to show why this is central to the Futūḥāt.

And so we'll look at this in three different ways or so but the first way, where all of this is explicit is in theطريقات (ṭarīqāt), in the lineages, in the spiritual lineages. So Ibn al-ʿArabī explains to us very clearly that, after the Prophet ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam passes away, there are two things that happen. The first is that the شريعة (sharīʿa) the outer Islām, the outward Islām, is transmitted and conveyed by عائشة (ʿĀʾisha) رضي الله عنها (raḍiyya-Allāhu ʿanhā, r.a.). And so ʿĀʾisha r.a. conveys the outward Islām. And then فاطمة (Fāṭima) r.a., his daughter, conveys the inner Islām, the ṭarīqāt.

So we have sharīʿa is conveyed by ʿĀʾisha r.a. and ṭarīqat is conveyed by Fāṭima r.a. So this is the way that this message continues to be propagated and to be as a wave form in the universe. And so what we look at then is this propagation from Fāṭima r.a.; we begin to learn the implicit, or the implied, or the quiet, or the secrets and these are the ones that are not necessarily broadcasted but the lineage holds them and conveys them. And one of the things a lineage conveys is that they take from ʿĀʾisha r.a.the statement that the character of the Prophet ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam is Qurʾān. So his character is Qurʾān.

And then if you look at الرحمان علم القرآن (ar-Raḥmān ʿallama al-Qurʾān, 55;4), so we look at ar-Raḥmān, the Supremely Compassionate, ʿallama al-Qurʾān, taught the Qurʾān; what we see in the lineage, when we enter into this—to the secret, we enter into a place where the نور محمد ﷺ (Nūr Muḥammad ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa-ʾālihī wa-sallam)—the Nūr Muḥammad ﷺ, is taught the Qurʾān. And then, خلق الإنسان (khalaqa al-ʾinsān)—created the human being. So the Prophet ﷺ was a prophet before Adam a.s. was between water and clay.

And so before humanity, there's the Nūr Muḥammad ﷺ who is taught Qurʾān; and then in theطريقة (ṭarīqa), we actually begin to look at the person of Muḥammad ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam as Qurʾān. This we know from one of the ways that we sing this in the إلاهي (ʾIlāhī)in the Jerraḥi tradition (الجراحي) and in that شيخ نور (Shaykh Nūr) translated, so it's in his words; we talk about يا علي (Yā ʿAlī), يا حسن (Yā Ḥassan), يا حسين (Yā Ḥussein), يا فاطمة (Yā Fāṭima), الم (ʾAlif Lam Mim). So these are the five under the cloak. So ʾAlif Lam Mim, this is a way of speaking of Muḥammad ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam; and also, حم (Ḥa Mim), يس (Ya Sin), طه (Ṭa Ha), all of these.

So what we then read when we look at سورة البقرة (Sūra al-Baqara), we have: الم (ʾAlif Lam Mim, 2;1), ذلك الكتاب لا ريب فيه (ḏhalika al-kitāb la rayyba fihi, 2;2)—that is the book that as no doubt in it. So who is that book? That book is ʾAlif Lam Mim, and that is Muḥammad, ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam.

So, we begin to see that the Nūr Muḥammad ﷺ is taught Qurʾān and then when the Nūr Muḥammad ﷺ takes bodily form in Arabia 1400 some years ago, that this becomes the person of Muḥammad, ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam, whose character is the Qurʾān and who is ʾAlif Lam Mim and who is the Qurʾān.

We'll look at some individual verses about this but let me go ahead and just read one passage Ibn al-ʿArabī has about this, about how the Qurʾān and the person come together—are the same.

So ʿĀʾisha r.a. was asked about the character of رسول الله (Rasūl Allāh, ﷺ) and she said, ‘His character is the Qurʾān.’ There is no verse in the Qurʾān, but the verse has a property in the heart of this slave, of Muḥammad ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam, because the Qurʾān descended for this.

So, “Rasūl Allāh, ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam, used to, in his reciting of the Qurʾān, when he passed through a verse of good fortune versus feminine, she would rule him to ask God for His excellence, and he would ask God for His excellence. And when he passed through a verse of torment and threat, ruling him to take refuge in God from it, he would take refuge. And when he passed through a verse, magnifying God, she ruled him to magnify God and he glorified Him with a character which this verse gave him, the praise of God. And when he passed through a verse of history, and what came to pass, the Divine Force in the centuries before him, the verse ruled the heeding of the lesson, so he heeded the lesson. So this is exactly looking over the verses of the Qurʾān and understanding the Qurʾān.”

So what we see here is that the Qurʾān, as it is being recited by him, and he's leading the prayer, he would respond to the verses and this is something when I first saw that years ago, in someone who would read, they would recite the Qurʾān and then respond to it in their own voice and own language, and it is quite beautiful. This is our سنة (sunna), that we respond to the Qurʾān as we hear it and even if we're the إمام (ʾimām) reciting the Qurʾān for the جمعات (jammāt), we still respond to the verses. So one of the practices in the lineage is that we have comments that come while we are reciting Qurʾān; and the same way that if there's a verse about threats and torments, we say I take refuge in God from that, so we're always interacting with Qurʾān. So this is the— his character is the Qurʾān.

Saqib

So Sidi before we explore particular verses of the Qurʾān could you just say something about the means through which Ibn al-ʿArabī interprets various Qurʾānic verses?

And the context of the question is, personally, I was really, really taken aback when I studied the Secrets of Voyaging with a parallel Arabic-English translation by Angela Jeffery. I was taken aback by how literally, on every line, there was a word or verse from the Qurʾān, you know, constant referencing, and I hadn't found that to that extent in the مثنوي (Mas̱navī) of Rūmī (جلال الدین رومي, Jalāl ad-Dīn Rūmī ), and not to say that isn't, you know, immersed or a commentary on the Qurʾān, I'm sure it's an ocean in and of itself, but to explicitly quote the Qurʾān, again and again, it was just quite mind boggling.

But then the second thing that took me back was the level of literalism Ibn al-ʿArabī brings to his interpretation, and by that I don't mean a dogmatic literalism, but almost a literalism which puts the infinite at almost—the infinite within the domains of the finite, saying that you do not need to go to X commentary or somewhere else, everything is enclosed within this finite domain; it's the ocean within the drop; and the way he was able to find the highest level of metaphysical meaning and depth within the subtle; within, you know, small nuances or subtle aspects of grammar, or letters, it was just absolutely amazing.

So could you say a bit more about that—his means of interpreting verses of the Qurʾān?

Shuʿayb

Right. Yeah, almost always his citation of Qurʾān is half a verse, or a clause of a verse. It's not very often a full verse and very, very rare that there's two verses. So what he's doing, as you say, the drop that contains the ocean; and he's looking at each word; and each word, and its position, has utter significance. And there's a reason for that. And there's a reason for how he is interpreting and that it's—not an interpretation; it's not a commentary, and let me kind of go into that.

So what happens is that he says that there's a special face of حق (Ḥaqq, ref. al-Ḥaqq) in every created being. And so every created being, every created being, has a special face and it's the first place that the تجلی (tajallī)hits; it is the first place the shiny, radiant Brilliance hits. And so each creature, each of us, and all of the creatures and all of creation has a special face, which is you could say, the mirror or the veil, or the place or the screen of a projection screen, where the light hits the projection screen, casts a shadow by the puppet, and what you see is what we call reality. That special face is the first place that tajallī place comes to and Ibn al-ʿArabī says that's the place where the Qurʾān was revealed, and the تورة (Torah), and the إنجيل (Injīl).

It's also the place that when we're in شورى (shūrā), so when we're in consultation, and when people are gathered in shūrā, in consultation, suddenly, someone will speak up and say something, and what that person says, will be revelation; what that person will say will be inspired; and at that moment, we know that that's the truth. And it could be a little kid; it could be an old woman, it could be a middle aged man, it could be anyone because what they'll do is they'll be speaking from the special face of Ḥaqq, which is in every created being where the Qurʾān was revealed, and the Torah was revealed, and the Injīl was revealed.

So Ibn al-ʿArabī goes to the special face. So when he's doing this writing, and he's telling us he's writing down what he saw etched in light in the photographed, acts of light in the youth, what he's doing is going to the special face that's in him, and he is finding out where the Qurʾān is coming from—the first place the Qurʾān is revealed.

And so when we memorize the Qurʾān, we have this very strange word إستسخار (ʾistiskhara), which is like from ضاهر (ẓāhir, ref. az-Ẓāhir), ظهر (ẓ h r), and it means to bring out the manifest Qurʾān. And the way you bring about the manifest Qurʾān is you go to the place where it was revealed and so when you're at the special face, you're standing with the Prophet ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa-sallam and جبريل (Jibrīl) عليه السلام (ʿalayhi as-salām, a.s.) is bringing a verse. So when you go to the special face, you are there at the moment of revelation.

And this is why the people who know the secrets get into trouble because then they're saying, ‘Oh, but the Prophet passed away,’ and all of these things but no, this is a living Nūr Muḥammad ﷺ, a living place, where the Qurʾān is a living Qurʾān.

And that's why ʿĀʾisha r.a. said, ‘His character is the Qurʾān.’ And so this special face, a verse has come to the special face, if you can go into that special face deep within, you will find the verse coming as it was first revealed and it is as if it's being revealed at that moment. And this is the place that you will sit there, stand there, be there with the Prophet ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam while Jibrīl a.s. is bringing a verse. And then this verse, when you get this verse, it then goes upwards; let's say it goes upwards into a more manifest place. And it goes upwards in seven different recitations. So these are the seven readings of Qurʾān. So it goes ورش (warsh) and it goes a حفص (ḥafṣ) and it goes up to the seven different places; and then it goes into translations and commentaries and it goes into Lex Hixon, Shaykh Nūr’s Heart of the Qurʾān. So it goes up in all of these places.

But what Ibn al-ʿArabī is showing us is that you can't go from the top and go down into the special face. You can't take the Qurʾān as it is recited and go backwards to the special face and understand it. So we cannot understand the Qurʾān exoterically from the outside, we can only understand the Qurʾān from the special face. So Ibn al-ʿArabī goes to the special face, and then says this is the special face.

So what we did for six months is we looked at the 114 chapters, corresponding to the 114 Sūras of Qurʾān in the Futūḥāt, and in these ones Ibn al-ʿArabī would say we're going to look at this lighting place. And now the lighting place might have been سورة الكهف (Sūra al-Kahf) or سورة يس (Sūra Ya Sin), it'll be some sūra and he'll go into the special face; and he'll describe in between six pages or 30 pages, he'll describe the special face of Ya Sin, the special face of Sūra al-Kahf, but he won't be quoting very many verses from Sūra al-Kahf.

Because I always wondered if you're going to be telling us about سورة الكافرون (Sūra al-Kāfirūn) let's say, wont you give us all the verses and go through each verse and explain them? He doesn't. He goes to the special face and gives us the insights, the truths of this sūra. And by citing other sūras, and other verses, and maybe one or two of the verses of that particular sūra. So that's because he went to the special face. And so you can understand the sūra by coming from the special face upwards but you can never go from the outward and the upper down into the meaning of Qurʾān and this is how Shaykh Nūr when he wrote the Heart of the Qurʾān, that's exactly where he is working from; he's working from the special face; and then it comes out in English, and it doesn't necessarily correspond to each verse; and it doesn't necessarily correspond to the Arabic translations; it's coming from the special face.

So this is the heart of Qurʾān. This is, Ibn al-ʿArabī is telling us, that if we want to understand the Qurʾān, we understand it from the special face.

Saqib

And so, this actually reminds me of two things. One, from a line of Rūmī when he talks about the shy bride, the Qurʾān is like a shy bride, if you want to approach her then do it through a friend i.e. one of those awliyāʾ who connect us with the special face. Presumably that's the same thing he's talking about? And then there's a beautiful poem by Iqbāl which he says, I’ll say it in Urdu first, “Tere Zameer Pe Jab Tak Na Ho Nazool-e-Kitab; Girah Kusha Hai Na Razi Na Shib-e-Kashaaf.”

So he says that until the book hasn't been revealed onto your heart or your conscience, then it remains a mystery whether you read, whether you're somebody who can write تخصيص (takẖṣiṣ) like فخر الدين الرازي (Fakhr ad-Dīn al-Rāzī) or you know like صاحب الكشاف (ṣāhib al-kashāf), all these commentaries really don't hold until it becomes— you read it from the special face.

And I think there is another story around that with Iqbāl. I’ll just mention it very quickly for any listeners who are interested, where he would recite the Qurʾān in the morning and his dad who was deeply inclined in fact, he had circles of Ibn al-ʿArabī I think they used to read the فصوص الحكم (Fuṣuṣ)together, funnily enough, and his dad would ask him every morning, ‘What are you doing?’ He says, ‘I'm reciting the Qurʾān.’ And then one day, he asked his dad politely, you know, ‘I recite the Qurʾān every day, and yet you keep on asking me what I'm doing.’ And his dad said, ‘Yes, when you recite, recite as though it's being revealed to you.’

Shuʿayb

That's it; that's beautiful. Yeah, this is the heart. And so I have two sentences here to read, well a few sentences, and this is from the Illustrated Guide.

“So the Qurʾān was sent down upon the heart of Muḥammad ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam. The Qurʾān never stops being sent down upon the hearts of his mother community, until the day of arising for judgment.” So the Qurʾān is ever fresh, it's always being sent down to the mother community every day.

“Thus, this descent onto the hearts is new, never getting old. So it is the perpetual revelation.” It's the perpetual revelation.

And “Learn, may God assist us and you, that the Qurʾān is a renewed sight descending flush against the hearts of the reciters of him, the Qurʾān, forever and ever. No one reciting him who recites him except based on a renewing, descending from God, the All-Wise and Apportioning, the All-Praise.’ So this is the living Qurʾān, the perpetual Qurʾān; every time we recite it is coming directly to the heart, to the special face, and we are reciting from there and this is what the mother community has access to.

And so when the Prophet ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam passed away, it became midnight. And when it's midnight, you don't know where you're going, you don't have any light, so your best thing to do is to grab on to manuals of فقه (fiqh), and stations of the soul, in ṭarīqāt, and all of that. So you fix things down, you write them up, you make manuals and you make instructions and you'll keep very strictly to these instructions because there's no light because you're in midnight. But when the third part of the night comes, the third part of the night when our Lord descends to the sky of this world and the third remaining part of the night asking—‘Is there anyone asking for their separation to be covered over?’ So we say, أستغفرك أستغفرك (ʾastaghfiruka), ʾastaghfiruka.

So we're in the third part of the night. Ibn al-ʿArabī says we're in the third part of the night so it's our time. So now we have the light, we have the living Qurʾān, we are closer to Muḥammad ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa-sallam than the people who were living with him. We are closer to him and when we recite Qurʾān, we can recite directly as the revelation came for the first time. So it is the perpetual revelation, the descent on the heart is always new. And so we are in the third part of the night, we're in a very special time, and so the Qurʾān then becomes living. And so this is when now when we say,الم (ʾAlif Lām Mīm),ذلك الكتاب لا ريب فيه (ḏhalika al-kitāba lā rayyba fihi)—that one, the ʾAlif Lām Mīm, is the book which has no doubt in it. And so this is the book that we read and this is the book which is Nūr Muḥammad ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa-sallam, because الرحمان (ar-Raḥmān),علم القرآن (ʿallama al-Qurʾān), he taught the Qurʾān and he taught the Qurʾān before there was human— وخلق الإنسان (wa-khalaqa al-ʾinsān)—before there was humanity, he taught the Qurʾān. To whom? The Nūr Muḥammad ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa-sallam.

Saqib

Ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa-sallam. So yeah that is what was one of my questions actually about the sequence within Sūra ar-Raḥmān as the why the Qurʾān is taught before humanity was created and then taught speech of علم البيان (ʿallama al-bayyān).

Shuʿayb

Yeah and this is always implicit, it’s always the secret; it's for each person to read those verses and begin to understand for themselves and this is طحقيق (ṭaḥqīq), they verify for themselves, as Ibn al-ʿArabī always tells us. We verify for ourselves the order of events, the order of events from outside of time and then inside time. And this order of events, this sequence, is in fact the story of creation. That's why there is a creation. So ar-Raḥmān then settles onto the cosmic Throne (العرش). And so this settling onto the cosmic Throne means that ar-Raḥmān will be the one who is overseeing all things and everything is in kindness and ends up in kindness; and the function of ar-Raḥmān is then to teach the Nūr Muḥammad ﷺ this Quʾrān. And this Quʾrān will come out when it comes into time, in the person of Muḥammad ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam in Arabia in 1400 plus years ago. And we're now in the third part of the night, so we now have direct access to our Lord who descends to the sky of this world.

Saqib

سبحان الله (subḥānʾllāh). So what's the next Qurʾānic verse?

Shuʿayb

Well, we could look at… so one of the passages I'm working on, I still haven't understood yet what to do with it and how to really handle all of it, but it's about the way that as you know, the Qurʾān in translation can be very difficult to read, especially people, a lot of seekers are people, in a sense, been wounded by religions and spiritual authorities and things like that. So a lot of seekers come to, if they're beginning to explore the Qurʾān, or explore Islām, these seekers will have had, you know, they've had enough trauma let’s say from the Old Testament, you know, from a very vengeful God and things like that. And the Qurʾān is often translated as if it's the Old Testament, it often feels to me that the translations are very much the same thing I'll read if I pick up the Old Testament, in a very harsh kind of translation. And so I've always been interested in finding out well, ‘Why is it that Ibn al-ʿArabī, when I read the Qurʾān in Ibn al-ʿArabī, I understand and it's beautiful?’ It's a thing of beauty. And yet, when I read it separately, I don't get that feeling. And I began to see that Ibn al-ʿArabī, well Ibn al-ʿArabī says that’s he had a dream where the كعبة (Kaʿaba) had bricks of gold and silver and he said in that dream, they said he saw the Kaʿaba made of gold and silver bricks and yet there was a brick missing; and then he says, ‘I am that brick.’

And so the way I understand that, is the brick that's missing, what Ibn al-ʿArabī does, is he gives us the full, complete universal Islām. You know, without Ibn al-ʿArabī, a brick is missing, and we can't understand the Qurʾān as something of beauty. And we can't necessarily understand the life of the Prophet ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam in a way that we can love and he becomes our beloved. We can’t understand this because we really need that last brick and that last brick is what Ibn al-ʿArabī does for us. And that's why every page has Qurʾān, every page has honoring of the Prophet ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam.

So this passage I'm looking at right now, he talks about people who see only beauty. “And so this is where the people of intimacy and beauty and kindness when they look into the Qurʾān, and into the things, all of them, their eyes do not fall on anything but something fine and beautiful. Not on anything but that, whatever it may be. When they recite the Qurʾān, no loathsome figures stand up before them.” So no ugly figures stand up before them; “Only what is contained there of the beautiful inflected.”

So he’s saying that these are people who when they read Qurʾān, they don't see loathsome figures, they don't see ugly figures, they don't think terrifying things. They see the beautiful inflected, and this word inflected, it’s very important, صرف (ṣaraf). So we say in English we have sans serif and serif fonts; so serifsare these these embellishments. And then ṣaraf is also a word where money changers so someone that takes the money and changes it into another form of money, another currency, that's based on صرفه (ṣarafa), صريف (ṣarrīf). And then in Urdu you have serif it’s also there, it is related. So, inflection is another way of looking at this word taṣarraf, and so inflection is when you inflect something. So they read the Qurʾān and they inflect the words in a way that is beautiful.

So we'll take one verse here, from Sūra 107,سورة الماعون (Sūra al-Māʻūn). So, اعوذ بالله من الشيطان الرجيم (ʾaʿoūḏhu billāhi min ash-shayṭānir-rajīm),بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم (bismi llāhi ar-Raḥmāni ar-Raḥīm), ويمنعون الماعون (wa yamnaʿūna al-māʿūn, 107-7).

Wa yamnaʿūna al-māʿūn; so Yusuf Ali has: “These are people who refuse to supply even neighborly needs.” So they deny the means of assistance. So they stop charity from being given. So this is a very strong sentence; it’s one that anyone will feel that this is very harsh and you don't want to really be feeling this and hearing this all the time.It's kind of depressing that there are people who refuse to give charity and Ibn al-ʿArabī is saying there are certain people who read the same verse, and they inflect it and here's how they inflect it.

So we're looking at this statement: “يمنعون الماعون (yamnaʿūna al-māʿūn)—they deny or stop up the means of help reaching. So these people, their allotment there, is where they veil the people from seeing the secondary causes. So they may turn their view towards the cause of them. The Causer, that’s Allāh. There is no helper but Allāh. So these are people who stop people from seeing that charity as being given by them. They want them to see only that Allāh is the one who gives. Allāh is the one who does. So they are told to say,إياك نعبد وإياك نستعين (iyyāka nʿabudu wa iyyāka nastʿaʿīn)—You alone do we ask for help. ”

You are not helped by the means of help reaching. So they want us to move and inflect this vision into: ‘You alone do we ask for help.’ So when they look at people who, when they look out and they try to deny that there's help being given to poor people, they're trying to stop help being given to the poor people, what they're doing is saying, ‘I want you to see that Allāh is giving charity to these people.’

Saqib

But Sidi, sorry to interrupt, but I’ve seen this happen previously as well with Ibn al-ʿArabī, we can see the potential permutation of meaning based on the linguistic meanings of the words, the Qurʾān, that are in the verse. However, if you then put that verse within context of Sūra al-Māʻūn, just two or three verses back, it says, فويل للمصلين (fa-waylun lil-muṣalīn)—woe onto the muṣalīn—the worshipers,الذين هم عن صلاتهم ساهون (al-laḏhina hum ʿan ṣalātihim sāhūn), الذين هم يرآؤون ويمنعون الماعون (al-laḏhina hum yu-rāʾoūn wa yamnaʿūna al-māʿūn), so those who worship in order to be seen, ostentation, you know, false piety and that sort of thing.

So, you know, and as you said, who then do not give in charity. So how would you then square that circle where it says, ‘Woe onto the worshippers,’ because that's who's being addressed?

Shuʿayb

Right. So what Ibn al-ʿArabī is doing here, and I'm still working on how to present this and how to work with this, in a way he's saying that there's certain people who when they hear Qurʾān they don't put their minds onto things that are terrible. There are terrible, horrible things in the world, no doubt about it. And there are evil, arrogant people, there are Pharaohs, and all of this, no doubt about it. But when they read it, they see a beautiful inflection. And so the question is, what is that beautiful inflection?

Like the ones who want people to see them, يرآؤون (yu-rāʾoūn),they want to be seen, these are ones who do something in order for others to emulate them. “The ones who know God in this community teach people the right action, seeking their education.” So these are persons who pray in order to be seen because they want other people to see how to pray.

So the first people we know them very well, the people who pray ostentatiously, and in a way Ibn al-ʿArabī’s saying, ‘When you're in love with the Divine, when you're in love with the Prophet ṣallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallam, you really don't care anymore about all these people who are ostentatiously praying.’ You're just sort of…

Saqib

Oh, I see.

Shuʿayb

You know, ‘I'm not interested in that.’ I'm interested in, ‘Wow! This verse is talking also, or inflectedly, about those people who are teaching.’ And then ساهون (sāhūn), the ones who delay their prayer or the ones who say, they're the ones who say, ‘That I'm not praying, Allāh makes me pray. Allāh makes me bend and do ركوع (rukkūʿ). Allāh makes me do ساجده (sājda).’ So all of this is in Allāh's hands. And so they're the ones who were saying, ‘I'm delaying the prayer, because I'm not the one praying. I'm not the one who has as effective action.’

So what he's saying is that when these people on this path who see only the beautiful, they see only the beautiful because they're in love. And when they're in love, all of the the ugly, petty things that are out there, the vicious things, the violent things, they're just not really interested in them. And when you fall in love, you end up realizing that you don't read the newspaper as much as you used to read it; you don't follow politics as much as you used to follow it; because that's—that's okay, that's what people do. But when you love you want to hear—you want to see all the beauty and you can see the beauty in every one of these verses, which sound very harsh or sound like, ‘Watch out you people who are praying!’ Well, of course we’re watching how we’re praying because I’m not praying, because if I’m praying it’s because Allāh made me pray. And so everything is shifted to the Beloved, and away from me.

Saqib

So he's essentially taking the focus away from almost like a human egocentric perspective to a theocentric حقيقة (ḥaqīqa) perspective.

Shuʿayb

Right.

Saqib

Where it's seeing the face, wheresoever you turn, there is the face of God.

Shuʿayb

Yeah and this is what Ibn al-ʿArabī does all the time and it's so helpful when he does that because I understand very difficult concepts in him when he starts saying, ‘Well, look at the way Allāh looks at it.’ And you say, ‘Oh, that's kind of crazy,’ but yeah, the moment you see it from Allāh’s perspective, then suddenly everything makes sense.

So it's really something because he does talk about, you know, the pettiness, the viciousness, the politics, and all of that and he says he was walking along the shore and he met one of the أبدال (ʾabdāl) and he just started talking right away about, ‘Oh, in this country, we have such an oppressive king, government, and the people are so misled.’ And you know, just complaining, complaining, complaining about politics; and so one of the ʾabdāl—the man responds to him, and he says, ‘Who are you to put yourself between the slave and his Master?’

So, you know, the slave is us, and the Master is Allāh. The creation is not my creation—it’s not made for me; and he says, Ibn al-ʿArabī at one point says, ‘Even the greatest of us forget that.’ We think the creation, it should be the way it works for me. But the grace is not for me, it's for the One who created it and the One who created it wanted all of these things to happen, so that the Divine Names would all have something to work on. So the Divine Names would have their their ability to work.

So why isn't everything expansive and generous? Because we need قابض (Qābiḍ,ref: al-Qābiḍ), we need constriction (قبض) as well.

So why isn't everything alive and healthy? Because we need theمميت (Mumīt, ref: al-Mumīt), the one who gives death.

So each of these Divine Names have their right. So all of these things have to take place. So the world is the most perfect world that there is—if you see it as the world that was created for the Creator, for the Creator's own desire.

And the world is not very nice if you look at it from my perspective because I wish people were not such jerks and I wish all these other things would happen.

And so Ibn al-ʿArabī says, ‘So if I'm in a situation, where the government is oppressive, and all these bad things are happening, I have two options: If I complain, and try to change things, then you know, I don't get any reward for putting up with it patiently. If I don't complain, then the government, the king, they're going to be in real trouble on the Day of Judgment (يوم القيامة) and I'll be fine because I just was… I'll be rewarded, it's good for me. If the king is good, and I have a good life, then my reward is the reward I get in this life, which I have a good life because I live in a country which is run by a very nice king.’

And so Ibn al-ʿArabī says, “So if you are someone who sees both worlds, then you have all the patience in the world when there is an oppressive tyrant in charge. Because you know that you will have goodness in this next world. ” And so what it does, and then again, these are hard to handle because that's not the way we're trained to see, but Ibn al-ʿArabī, he is a conveyor, a Dragoman of love, of عشق (ʿishq) and passion; and so when you are in love—the newspaper doesn't have the same impact. So you say, ‘We'd like to read the newspaper, we'd like to gaze at the face of your Beloved.’ There's your choice; it’s pretty obvious.

Saqib

So Sidi, I think this is a really interesting point. I mean, it's the 14th of April today 2022 and if I can slightly sort of off-track, just slightly, just based on what you've just said. There's huge amounts of turmoil in the world from Ukraine to Pakistan. I've been following that quite intensely, in fact, and, yeah, the overthrowing of Imran Khan's government and the whole, you know, the masses of people sort of coming out to make a stand. I get the perspective of, sort of, you know, the Daoist monk, what is ‘is’—and you know, I don't oppose it, I accept everything as it is because it's Divine Will, but on the other hand, Islamic history is replete is filled with the warrior-saint archetype from Emir ʿAbd al-Qādir Jazaʾiri, Tipo Sultan and others who have made the stand in the face of oppression to the unjust King because it’s all selfless manifest aspects of جلال (Jalāl, ref. al-Jalāl) and قهار (Qahhār, ref. al-Qahhār), you know, which are very evident. And, in a sense, I think it's very interesting, obviously whatever we think about Imran Khan, people sort of agree or disagree, but he seems to be somebody who's very rooted in faith. He starts off with,إياك نعبد وإياك نستعين (ʾiyyāka naʿbudu wa iyyāka nastaīn)and our slogan isلا إله إلا الله (lā ʾilāha ʾillā-llāh) and now we have to embed it and stand for serving none other than the One (الأحد), not some political agenda or money or power or status, we have to make a stand. So, surely that is also a manifestation or a practical application of spirituality? Because it's a… there's some element of selflessness involved in that?

Shuʿayb

Yeah, this is how Ibn al-ʿArabī always takes us back to where we attribute things. So do we attribute to ‘me’ or do we attribute to Allāh?

And he says, so from Qur’an we understand that you attribute the bad things to myself and I attribute good things to Allāh, and then they all come from Allāh. And so with this, the way that we handle this is if you're going to—and we have theحديث (ḥadīth) about, you know, that if there's injustice that you stop it with your hand, your mouth, or your heart. And what this is doing is, and actually the most important is the heart one because then everything else follows. So if I oppose with my heart, then I understand what my position is.

If I attribute things to myself, like, I'm going to make a political movement, and I'm going to encourage five people, we're going to go off and do something, and I'm attributing it to myself, then that kind of activism, well if it fails, it's very devastating. You know, it's exhausting, it's exhausting to fail when you fight against the tyrant. But if I say, if I attribute all to Allāh, then I attribute that my job right now is to do this or that, and I do that not for my sake, or not for the sake of the goal, like overthrowing a tyrant, but for the sake of Allāh, then I have all the energy in the world. So if it fails, I didn't fail—it's not me failing. And so I'm doing what I need to do. And so this is how we are always—‘They will not forget except,’ الا ما تنسى (illā mā tansā), ‘Only what we are made to forget,’—and we were made to forget that Allāh does all; so then we think that we do something and then we need to forget that.

And so there's always this, there is activism, there is standing up for justice, all of these things. The only way, what we find is that when we stand up for justice without having had that in the heart, but only in the hand, if it's in the hand, then it can be violent, and it can be violence versus violence and there's really no difference between them. If it's by speaking, it's the same thing, we've just complained about things. But if it starts out with the heart, and then the mouth and then the hand, then something is quite different. And that is to note when you look at something you say, ‘This is wrong,’ and this is Ḥaqq and that is what the heart does, it says this is wrong, and if it's wrong, then we stand up.

But you see, Qurʾān says, ‘And do not broadcast ظلم (ẓulm),’ do not broadcast oppression, except in cases of injustice. And what that is saying is that we don't go off and identify all of the time oppression. When we do see oppression that needs to be opposed, we oppose it as slaves; not as, ‘The Master made a mistake,’ you know, ‘The Master made a mistake and I put this tyrant in place.’ I oppose it as a slave saying, ‘The Master wants me to do this and that's what I will do.’ And then I have all the energy in the world.

And so each person, the same way with إجتحاد (ʾijtiḥād), the same way with sharīʿa, each person has to decide what is the situation and what is my response to this situation. And the response to a situation has to come from the heart and then we'll find ourselves having strength and encouragement and we won't be devastated if something fails.

So this is the way Ibn al-ʿArabī wants us to move and so the key is that we're doing this not because we're trying to make the world a better place. Because the world is perfect the way it is. We're trying to do this because: Which of the Divine Names are going to be dominant right now? And is there going to be justice or injustice? And so you fight for what is just, and if injustice prevails, then injustice prevails; then you die the martyr, in other words, you give up but you give up because you can't do anything else and there is no failure at that point, then you're alive, you're شهيد (shahīd). And I don't even mean physical dying, I mean, mentally you prepare yourself to do something, and you want to do something, and you're thwarted, you're not allowed, you're not able to do that, then your intention means everything. So there's going to be activity and action and movement and all of these things, but the key is to understand where it's being attributed; and for my sake, it's important that I attribute whatever action I do to Allāh, and then watch those Divine Names work within me and in me.

Saqib

That's wonderful. Sidi, can I just before we sort of move on, but just going back to the Sūra al-Māʿūn, just to put my mind at rest, what do you do with the starting of the verse where it says, فويل للمصلين (fa waylun lil muṣalīn, 107;4); so: Woe to the worshippers. So there's a clear Arabic word saying, you know, showing some sort of disapproval before the rest come. So you've given much lovely commentary on the Akbarian perspective on these other inflected meanings, but how would you inflect the first verse there?

Shuʿayb

So it's it starts out: fa-waylun—so, ‘Woe to,’ or ‘Be careful,’ or ‘Watchful, ‘ or ‘Be alert for,’ and ‘Problems are there if…’—if you are someone who is praying. So I am someone who is praying, I have to be very careful, and there'll be woe to me if I say: ‘I am the one praying’; and I've got the big ‘I’, the big arrogant ‘I’ there. If I say that Allāh is the One who prays and blesses Himself, if I say that I am the one whose movements are given by the One who does, the فاعل (fāʿil), Allāh is the only fāʿil,the only One who does, and I attribute the prayer to Allāh, then it is a beautiful thing. If I attribute the prayer to myself, then I should be warned and someone needs to warn me. It's a ‘watch out for’ with your attributing the prayer to yourself; so I do not attribute the good that I have to myself.

So by آدب (ʾādab) I attribute the bad to myself but I attribute the good to Allāh and that's why in Muslim societies and cultures we always say ماشاء الله (māshāʾllāh). We say, when you see a child does something good, you say māshāʾllāh, because what you want to say is to the child is you're a wonderful person, but don't attribute it to yourself, attribute it to Allāh, and that's the way to live a life so: Māshāʾllāh. Allāh made you do something beautiful and recite that poetry so well or to do your homework so well, that was māshāʾllāh, that was Allāh did that.

Saqib

Subḥānʾllāh. So Sidi, the next verse, do we have time for another verse? Maybe Sūra al-Kāfirūn?

Shuʿayb

Okay. So the people who are the كافر (kāfir), so kāfir comes from كفر (kufr), which means to cover.

So let me see… so kāfirūn; the kufār, the kāfirūn. “So these are the ones who cover up their station.” So cover up,كفر (kafara) is to cover, and ستر (satara) is to cover. “These are the one’s who cover up their station; for example, the ملامتية (the Malāmatiyya),” so the people who blame themselves; so “the Malāmatiyya are very careful making sure that their prayer, fa-waylun lil muṣalīn, their prayers are always attributed to Allāh.”

“And so when they're in a mosque, they never stand in the same place. They never do more than two ركعة (rakʿa) of sunna. They never do anything that makes people look at them because they don't want anyone to see them as special. And so they do the absolute minimum of Islām, so that no one looks at them. So they they are blamed for not being more pious, and they blame themselves for trying to be pious.” And so they're the ones who Allāh is jealousy protective of, so no one should see them, and so they are the shy brides. “That no one should see them and no one should know how special they are to Allāh.” So they will never pray in a way that makes people look at them or makes them think that: ‘I'm praying; I'm such a great guy doing so many prayers.’ And so they always attribute it to Allāh.

“And the kufār, the ones who cover up, are the cultivators because they cover the seeds in the earth,”—and that's where the rest of this translation—and we already read this, “This is where the people of intimacy and beauty and kindness, when they look into the Qurʾān and into all things, their eyes fall only on what’s fine and beautiful, whatever it may be. When they recite the Qurʾān, no loathsome figures stand up before them, only what is contained there of the beautiful turned about.”

So the kāfir is someone Allāh has sealed over his heart and his ears and put over his sight a gauzy veil. The كافر (kāfir), among the awliyāʾ, is someone the True has sealed his heart. You see Allāh has occupied this person's heart to make it His house. ‘My earth and my heaven are not vastly spacious enough for Me, but vastly spacious enough for Me is the heart of my slave.’ Allāh is jealous, and He does not want a single one of His creation, competing with Him for the heart. No one else should be in that heart.

“It is just as He sealed off the Sacred Precinct, the حرم (Ḥaram), which is the Kaʿaba, so it is not lawful for anyone to hunt its animals or to cut its trees. Indeed, Allāh looks only at the heart of the creature. So when Allāh seals over the heart of you, this creature, no one but your Cherisher enters in your heart, and he sealed over your hearing, so you do not attend to the speech of anyone only to the speech of your Cherisher. Thus, they turn away from main speech, and over their sites is a gauzy veil. This is a covering of grace, thus they never look at a thing but they see signs pointing to Allāh. This veil interposes between the eyes and any sight which would be without indications to Allāh. This veil interposes between them and whatever is inappropriate for them to look at.’ So this is a praiseworthy veil, and they have عذاب (ʿaḏhāb), so ʿaḏhābmeans torment, but ʿaḏhāb also meansعذب (ʿuḏhub), sweetness. “So you see Allāh called it a torment using this noun as a favor to the mu’minūnbecause the faithful will find sweet,يستعذب (yastaʿiḏhubu), from عذب (ʿaḏhaba), so we'll find ʿaḏhāb to be sweet, what is painfully felt by enemies of Allāh. So it is a torment for these.”

So Ibn al-ʿArabī is saying that because Allāh is jealous of these special creatures, He seals their heart and He seals their ears so they can't hear anything and He covers over their eyes with a veil so they can't see things that they shouldn't be looking at. So they only see the beautiful; they only see Allāh; they only see into their heart; and so these are the special people who are the kufār— they are kāfirs among the awliyāʾ.

Saqib

Well, so just to be clear, I've actually got Sūra al-Baqara in front and you've sort of answered my question before I've asked it… بسم الله الرحمان الرحيم (bismi llāhi ar-Raḥmāni ar-Raḥīm) إن الذين كفروا سواء عليهم أأنذرتهم أم لم تنذرهم لا يؤمنون (inna al-ladhina kafarū sawaʾun ʾa-ʾanḏhar-tahum ʾam lam tunḏhir-a-hum lā yuʾuminūna, 2:6) ختم الله على قلوبهم وعلى سمعهم وعلى أبصارهم غشاوة ولهم عذاب عظيم (khatama Allāhu ʿalā qulūbihim wa ʿalā samʿihim wa ʿalā ʾabṣarihim ghishawatun wa lahum ʿadhabun ʿaẓīmun, 2:7)

As for those who persist in كفر (kufur), disbelief, it is the same whether you warn them or not, they will never believe they will not have faith. And so Ibn al-ʿArabī is not denying the literal exoteric meaning that there is kāfirs who this apparently applies to, but is also saying there are multiple, this verse is pregnant with multiple levels of meaning almost, and one of them applies to the awliyāʾ, who cover their station from people, and Allāh has sealed—khatama Allāhu ‘alā qulūbihim—Allāh has sealed their hearts, hearing, and their sight, so you can't preach to them because they see nothing but the Divine. I mean, that's a very high station of the Malāmatiyya and that was what I was going to ask you: wa lahum ‘aḏhabun ‘aḏhīm—it's similar to fa-waylun lil muṣalīn, you know , the woe onto the disbelievers, but the ʿaḏhāb—what about the ʿaḏhāb then? What happens? Obviously he's said, going back to the literal meaning of ʿaḏhāb,from the root ʿaḏhaba, there's a sweetness there as well.

Shuʿayb

Yeah.

Saqib

Then what about if we then take that perspective, when we look at like Sūra al-Kafirūn,قل يا أيها الكافرون (qul yā ayyuhāl-kāfirūn, 109-1) لا أعبد ما تعبدون (lā a'budu mā ta'budūn, 109:2)—I do not worship what you worship. You know, there's a clear distinction, ولا أنتم عابدون ما أعبد (wa lā ʾantum ʿābidūna mā aʿabud, 109:3)—nor will you worship that which I worship, ولا انا عابد ما عبدتم (wa lā ana 'ābidum mā 'abattum, 109:4)—and I shall not worship that of which you worship, ولا أنتم عابدون ما أعبد (wa lā antum ʿābidūna mā aʿabud, 109:5), لكم دينكم ولي دين (lakum dīnukum wa liya dīn, 109:6)—nor will you worship that which I worship, onto your religion and onto me mine. So there is a clear—not duality but distinction, between us and them there, and so how do you square that?

Shuʿayb

Well, so let's look at three things and make sure I get all three of these things in. So we’ll let’s start with that one and so that is that Ibn al-ʿArabī’s position is that عقيدة (ʿaqīda), there are قاعده (qāʿidah), there are infinite number of ʿaqīdas, every human being has their own ʿaqīda. We can agree on an ʿaqīda, we can all agree and say that we'll believe in the books and the angels and things like that but, when it comes to the تجلی (tajallī) of Allāh, Allāh never repeats twice to one person and never gives the same to two people.

So if Allāh never reveals Him/Her/Itself the same to two people, then the Allāh that I worship is not the Allāh that you worship. Because I see Allāh, and you see Allāh, and Allāh never repeats, so we can never be in the sameدين (dīn). That’s why we call it the dīnof Allāh; Allāh's dīn is that everyone will have a separate different, unique vision, and religion and belief system. And so then the second one is of: لا يؤمنون (lā yuʾminūn)—so you can warn them or not warn them they're not going to have faith because faith is belief in the unseen. And so these ones they look into their heart which has been sealed up and only Allāh is there because it's been sealed and when they look at Allāh, they see Allāh, so it's not based on the unseen. So they don't have faith in Allāh, they have sight of Allāh, because Allāh resides in their heart. And then as you’ve said, wa lahum ‘aḏhabun ‘aḏhīm, they have this great torment.

So Ibn al-ʿArabī does it two times. The awliyāʾdo have a great torment in this world; they do have a great torment because when the prophets and the messengers speak to them, they don't listen to them, and so when they don't listen to them, it looks like they're not going to be guided, and if they're not going to be guided, they're going to be in trouble. And so they do have a great torment in this world because they're not able to function the way the rest of us are able to function. Because they're the lovers and these are lovers who are tormented because nothing satisfies them except Allāh and they are always searching for Allāh, they are always waiting for Allāh, they're always loving Allāh; and so they do have a great torment. But, they also have a great sweetness and that is ʿaḏhāb, إستعذب (ʾistiʿaḏhaba) means to seek out sweet water. So, ʿaḏhāb is torment, and ʾistiʿaḏhaba is to seek and get sweet water. So their torment turns into sweet water and this is how even the people in the hellfire, inجهنم (Jahannam), that their torment will turn into sweet water and it turns into sweet water when جبار (Jabbār, ref. al-Jabbār) puts the foot on Jahannam and says that's it, and seals Jahannam; and the people who are in Jahannam are the family of Jahannam; and her sister is جنة (Janna), and there are people who are the family of the Janna and there are people of the family of Jahannam, the two sisters. And when that sealing takes place, their torment turns to sweetness, because all will end up in رحمة (raḥma). Everything will end up with raḥma, whether they're in the hellfire, which will turn sweet or whether the Jannawhich will be mild climate and and sweet.

So Ibn al-ʿArabī takes there to be multiple meanings and each of these can speak to a particular insight and that's because if you go to the special face, you can then branch up into—they'll taste—they will have a tremendous torment. You can bring that up to this and the tremendous torment in this world, even of the awliyāʾ, who suffer because they're lovers of Allāh. You can bring that up to sweet water, that they will actually have sweet water, it will be sweet for them; when their hearts are sealed and the ears are sealed, it will be sweet for them because all they hear is Allāh. And then you can bring it up into another one, that those whose hearts, whose ears are sealed and they don't hear the prophets a.s., they do have torment, they do get a tremendous torment because they're unable to be guided.

So the special face gives the reality, the Truth, and then it comes out up into three different ways, right, just right there, and there'll be more than those three different ways.

Saqib

That's wonderful, thank you Sidi.

Thank you Sidi, should I call you Dr Eric Winkel? Dr. Winkel or Shuʿayb?

Shuʿayb

Well, we're talking about Ibn al-ʿArabī so Shuʿayb is the best because when I took on the name Shuʿayb I took it on as I was reading Qurʾān and there was, you know, the Prophet Shuʿayb a.s. and I thought, ‘Well, that's a name I could take on,’ so I took on that name and then years later I realized that Ibn al-ʿArabī’s best friend is شعيب ابو مدين (Shu‘ayb Abū Madyan).

Saqib

Wow, subḥānʾllāh.

Shuʿayb

So when talking about Ibn al-ʿArabī I go by Shuʿayb.

Saqib

Super, thank you Sidi Shuʿayb; absolutely wonderful talking to you again. May Allāh bless your Ramadan and put بركة (baraka) in your work and we really look forward to further conversations in the futureإن شاء الله (ʾinshāʾllāh).

Shuʿayb

Yes, so thank you very much, الحمد لله رب العالمين (al-ḥamdulillāh rabbi l-ʿālamīn).